Third Ryde Tube: Transfer Troublesome

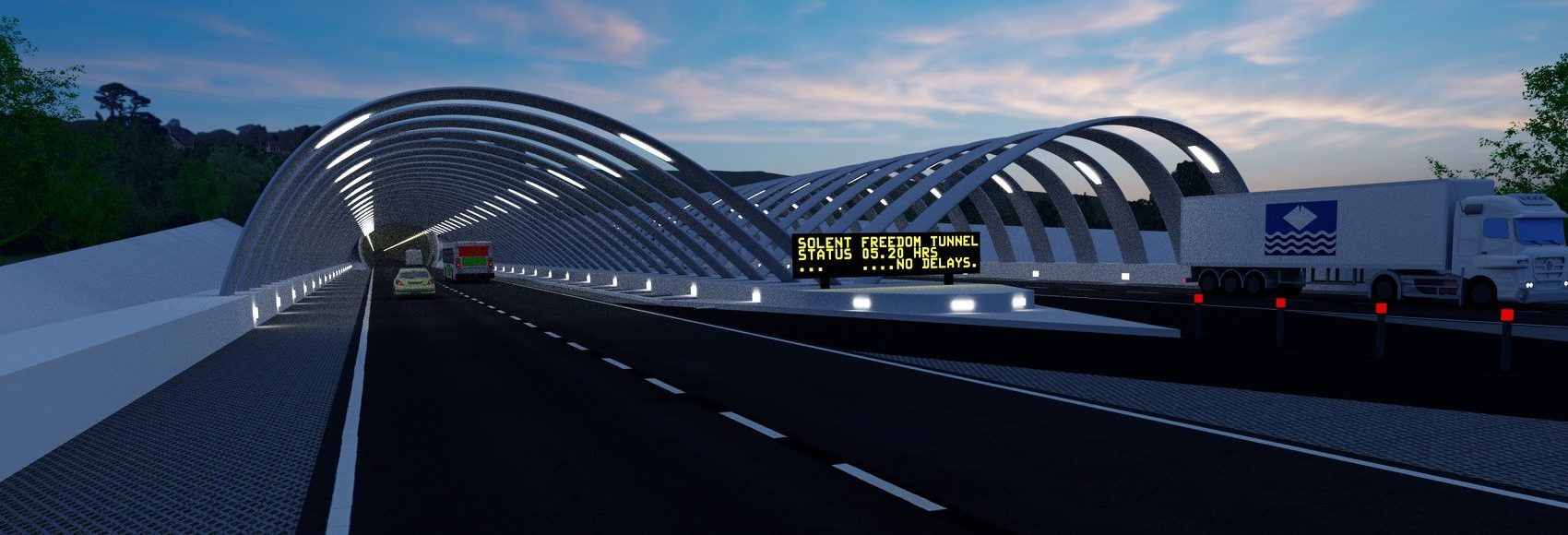

The idea for some, is that a rail tunnel may be a better solution than a road tunnel across the Solent Waters. PRO-LINK believes that a rail tunnel has little benefits above existing sole ferry option… click here for more information

236 comments

London Tube trains regularly operate on a line that never appears on any Tube map. As one of the few examples of Underground car cascading, retired Tube trains have been operating on the Isle of Wight’s Island Line since 1967.

This special relationship has lasted for decades, with two generations of retired Underground trains migrating south, like people, to retire by the seaside.

But this time round as replacements are sought once again, the apparently simple solution of buying in a third generation of time expired Tube stock looks less likely, as a host of other problems have come to the fore. The problem is working out what comes next.

The current generation

Class 483s at Ryde St John’s Road in 2017 (author)

When the Isle of Wight’s railway was electrified in 1967 by British Rail (BR)’s Southern Region, they imported ex-London Underground Standard Stock dating from the 1920s to comprise the train fleet. The Island Line’s Standard Stock, in turn, was replaced in 1989-90 by 1938 Tube stock, brought in by Network SouthEast (NSE). Now, nearly 30 years on, it will soon be time for the 1938 stock’s replacement as well.

The Island Line was electrified at the same time as, and had economies of scale with, the Bournemouth electrification project. Whilst the former had been specified to operate 7 car trains up to every 12 minutes, it has degraded significantly in recent years.

What is Island Line?

Isle of Wight railway map (DfT)

Isle of Wight railway map (DfT)

Island Line runs between Ryde Pier Head station, half a mile out to sea (at high tide) on the north-east coast of the Isle of Wight, and Shanklin on the Island’s south-east coast. There are six intermediate stations, and the line is all that remains of a once island-wide railway network. Whilst the remainder closed to regular passenger service, the Ryde Pier Head to Shanklin section was electrified. It is single track south of Smallbrook Junction station, where connections can be made with the preserved Isle of Wight Steam Railway, and there is a passing loop at Sandown. The down line between Ryde Pier Head and Ryde Esplanade is currently rusting and unused, with that section now effectively operated as a single track railway.

The third dimension

Ryde Tunnel (Wiki Commons)

The reason for the use of Tube stock, and by extension the unusual association between railway operations under London and on the Isle of Wight, is the restricted clearances in Ryde Tunnel and under Bridge 12 near Smallbrook Junction. The maximum height of rolling stock on the line was limited to 11’ 8” (3.56m) even in steam days, some 25cm less than on the mainland. When the line was electrified, BR Southern Region took the opportunity to raise the track bed in Ryde Tunnel by another 25cm, in an only-partially successful attempt to address recurrent flooding problems there. Being close to the sea, and the track bed being lower than sea level, flooding risks have been ever present.

Ryde Esplanade flooding (Wiki Commons)

The raising of Ryde Tunnel’s track bed in 1967 made the height restriction even more severe. The headline figure for the current maximum height of stock is approximately 3.3m, though much depends on the interaction between the curved roof of the tunnel and the roof profile of trains. A train which is just under 3.3m in height might fit at its centre line, but not at its outside edges. At the time of electrification, the only easily available trains small enough to fit through Ryde Tunnel were the Tube’s Standard Stock, at 2.88m in height.

Nomenclature

The lack of the definite article in “Island Line” is on purpose, being the brand created by Network SouthEast in the 1980s and which has become ingrained, in the same way as people refer to “Thameslink” rather than “the Thameslink”. To its credit, the current train operating company (TOC) has kept the moniker.

What’s the Problem(s)?

The existing fleet of Class 483s (as the 1938 stock was classified on the BR ‘TOPS’ locomotives and rolling stock numbering system) is 80 years old and can’t go on for much longer. The Class 483 fleet was nine strong when it arrived, with a tenth unit for spares, but due to ageing and seaside corrosion it has steadily been contracting ever since.

Ex-GNER Chief Executive Christopher Garnett undertook a study into Island Line in 2016 for Isle of Wight Council during the South Western refranchising process, of which Island Line is currently (a minute) part. At that time he found that just five of its trains remained serviceable.

Dino 483 at Ryde Pier Head in 2005 (author)

A sixth, unit 002 ‘Raptor’, is out of service and makes for a forlorn sight, slowly being cannibalised outside Ryde St Johns Road depot. The current peak timetable requirement is for just two trains, so a fleet of five trains sounds sufficient, but in fact the ageing trains are getting increasingly unreliable. One of them suffered a minor fire at Ryde Pier Head last November. The saline environment in which they operate takes its toll on the Class 483s (as the state of their roofs often shows) and with scheduled maintenance requirements, train availability can be tight. Despite that, Island Line maintains impressive punctuality and reliability. 99.3% of services arrived with five minutes of schedule in the 12 months to January 2018, and 99.6% of services were operated.

Although the Class 483s are two-car trains, platforms are long enough to accommodate four-car formations. These operate during the summer months, when the additional capacity is helpful in dealing with the large groups of tourists arriving from Wightlink’s high-speed catamaran ferry once or twice hourly, which sails between Portsmouth Harbour and Ryde Pier Head stations. Additional ferry passengers join and leave trains at Ryde Esplanade upon transferring with Hovertravel’s hovercraft service to Southsea.

Ryde Esplanade station and hovercraft, Ryde Pier Head in distance (author)

The Wightlink catamaran ferry (Portsmouth Harbour to Ryde Pier Head) operates twice an hour Mon-Fri peak hours (not quite every 30 minutes, the headways are 25/35 minutes), spring/summer Saturdays and occasional summer weekdays. Otherwise the service is hourly. But only one Island Line train per hour connects with them in a timely fashion, particularly in the southbound direction.

The fourth dimension – Time

Twice, ex-London Underground Tube stock has been brought over to the Island to meet Island Line’s unusual rolling stock requirements, so why not thrice?

The first reason is that it looks unlikely that any Tube stock will become available within an acceptable time frame. Despite Transport for London’s decision to sell and lease back Elizabeth line trains to release funding for a replacement fleet of Piccadilly line trains, 2023 would seem to be the earliest that the existing Piccadilly line 1973 stock might become available. By that time the Class 483s will be 85 years old, assuming they survive that long. As we’ll see later, there is no certainty that will be the case.

Furthermore Ryde tunnel is not only low, but has a tight reverse curve with a combination of single and double track bores. Yet the 2016 Garnett report didn’t mention the tunnel curvature specifically, but instead noted that Piccadilly line 1973 stock wouldn’t be suitable for transfer to Island Line because of the curvature at Ryde Esplanade station, which is also quite severe. There are actually two related issues, getting the longer 1973 stock carriages round the curve without fouling the platform, and the distance from the platform of the doors at the carriage centres when stopped at the station. This would be a particular problem at Ryde Esplanade station, which is tightly curved.

Vivarail’s refurbished ex-D78 trains have often been suggested as a potential Island Line rolling stock solution. Being approximately the same height as mainline rolling stock, they would require the trackbed in Ryde Tunnel to be re-lowered, but even then they might not be suitable. The 1973 stock driving cars are 17.47m long. The D78 driving cars are 18.37m long. So if a 1973 stock carriage is too long for Ryde Esplanade station, a D78 is even longer. Until someone performs a proper gauging exercise, it’s impossible to rule replacement vehicles in or out.

Ex-Bakerloo line 1972 stock was another possibility considered by the Garnett report, but on current plans it would not be available until after the Piccadilly’s 1973 stock is retired, and the date when the Deep Tube Upgrade might allow its release seems to be receding.

Conversion of 1972 stock to two-car operation on the Island would be more complex and expensive than it was for the 1938 stock, which had its traction equipment located in the driving trailers. The 1972 stock, on the other hand, has some of its traction equipment spread under trailer cars, and this would need to be transplanted to the driving trailers.

The Standard Stock was 40 years old when it arrived on the Island, and the 1938 stock was just over 50 years old. The 1973 stock would be 50 years old on arrival even if it were deemed suitable and made available, whilst 1972 stock would probably be nearly 60 years old by the time it arrived. In a world in which Northern’s Pacers are finally being replaced by modern trains, many Islanders are getting fed up of having decades-old London Underground cast-offs dumped on them.

The second, and probably more urgent, reason that a third generation of ex-Tube stock is unlikely on the Island is that the Class 483s are coming to the end of their natural lives at the same time that every other part of Island Line, signalling, power supply and track, seems to be doing exactly the same. There is a perfect storm of simultaneous technological demise taking place.

Whilst we’re at it, what else is wrong with Island Line?

As mentioned, four-car formations of Class 483s are helpful in dealing with tourist loadings on Island Line during the summer months, but it is clear when such operations are undertaken that something is amiss. Passengers never see both timetabled trains in four-car formations, even in the height of summer. One runs as a four-car formation, and the other as a two-car.

483 interior in 2017 (author)

483 interior in 2017 (author)

On summer Saturdays shortly after electrification (the changeover day for weekly holidays on the Island), the timetable saw six 7-car trains providing a 12-minute headway service along the line. This was the maximum level of service, using nearly all available carriages.

However Garnett’s study found that today, Island Line’s third rail power supply is no longer robust enough to allow two four-car trains to run at once. The voltage drop along the line is apparently so severe that at Shanklin, the third rail is only supplying some 350V out of the normal 630V, which explains the leisurely get-aways passengers experience at that end of the line.

Two trains per hour appears to be sufficient to handle current peak patronage levels, but the current timetable is inconvenient with headways between trains of 20 minutes and 40 minutes. The uneven spacing of services is a legacy of the decision to retain a passing loop at Sandown rather than Brading so that a 20/20/20 minute headway train service could be operated (although such a timetable hasn’t operated since 2007, when it did so on summer Saturdays).

Train strip map in 2018 (author)

Whilst an evenly-spaced 30 minute headway would make journey planning along the line generally easier, the drawback of the current 20/40 minute headway timetable is most noticeable for its impact on ferry connections at Ryde Pier Head.

As the track condition has deteriorated over the years and is now poor, so too has the ride quality of old trains suffered. Maintenance arrangements are unusual at Island Line. It is vertically integrated, with the operator leasing the infrastructure from Network Rail – but only down to 450mm below the rails. The Ryde Pier Head station itself looks in need of refurbishment, while piers themselves impose severe maintenance workloads due to the hostile saline environment in which they are located. Luckily for Island Line’s operators, the Pier itself is not part of the vertical franchise and remains the sole responsibility of Network Rail – but given Network Rail’s other pressures on the mainland, Ryde Pier appears not to be a high priority.

Adding to these obvious issues is the fact that Island Line runs at a considerable loss. Although exact figures aren’t easy to come by, Garnett quoted annual revenue of approximately £1m against costs of £4.5m. Assuming that station entry/exits are a reasonably proxy for passenger journeys and that most trips are within the island, the most recent ORR statistics show 628,446 journeys (1,256,892 entries plus exits) when Island Line’s eight stations are taken together. That works out as a subsidy of over £4 per passenger trip. [These figures have been revised to 628,446 entries as the exits were also island based. Which takes the subsidy for each journey by each passenger to £8 per trip. Unsustainable.]

The daily ridership average is almost 7,000 journeys a day, but in reality is significantly higher in the summer and correspondingly lower in the winter.

None of the problems Island Line faces have cheap solutions, and it is clear that revenues are not a source of funding given that the line doesn’t come close to covering its running costs. Although a micro-franchise has been suggested in the past to focus on improving the line’s financial position (indeed, at the first round of rail privatisation Island Line was a separate franchise) it has never been clear who would fund its subsidy requirement apart from central government. Garnett noted that the Isle of Wight Council “would not have either the financial resources or skills to be able to operate the Island Line franchise.”

Being part of the wider, profitable, South Western franchise means that Island Line’s losses are covered by profits made elsewhere, but the line has received scant attention from franchise owners since its incorporation into the South Western franchise.

Integrated fares

Visitors can already take advantage of co-fares with Island Line and other transport:

- Day Rover passes (£16) allow unlimited travel on Island Line and the Isle of Wight Steam Railway.

- Return tickets from the mainland cover ferry/hovercraft travel, Island Line from Pier Head to Smallbrook Junction, then Steam Railway.

The ferry and hovercraft serving Ryde are passenger only, so Island Line is ideally situated to cater for their custom. The car ferries to/from the mainland alight at other Isle of Wight ports, the closest being a few miles away.

New franchise, new consultation

The new South Western Railway (SWR) franchise, operated by First/MTR, began in August 2017, although the new company hasn’t yet got round to replacing the signage at Ryde St Johns Road which states that previous franchise operator Stagecoach is still in charge. As part of the new franchise, First/MTR committed to a “key relationship with the Isle of Wight Council and other stakeholders to develop a more sustainable future for Island Line. South Western Railway will now start the consultation phase of the process to deliver improvements for Island Line. This will include setting out a range of options to stakeholders for rolling stock and infrastructure, before submitting ideas to the Government next year.”

A formal consultation document was issued in late October 2017, but the exercise wasn’t a full public consultation, remaining unpublished on SWR’s website, and being conducted instead with local stakeholder groups. Independent watchdog Pressure group Railfuture published the consultation document anyway, and it made for interesting reading. Not only did it recognise the obvious problems detailed earlier, but it revealed that Island Line’s situation was even worse than had previously been assumed.

For a start, SWR revealed that only three Class 483 trains are currently serviceable; in other words 100% availability is necessary to run the summer two-car and four-car train service. Island Line is just one serious technical failure away from having too few trains to run its summer timetable at full capacity. And because the Class 483s are owned by the franchise, rather than leased, any conventionally-leased replacement trains will add to Island Line’s losses. Confirming that operating costs are around four times higher than revenue, without putting exact amounts to them, the consultation document summed up Island Line’s current challenges by reiterating some of the well-known issues and highlighting others as well:

- Class 483s do not have a modern on-board customer experience nor meet customer expectations. Given modern rail passenger expectations for features like Wi-Fi, power sockets, on-board digital information displays and the like, it is questionable whether a practicable conversion programme could ever meet them.

- The 40-minute / 20-minute headway does not serve customer needs.

- Revenue protection is challenging: guards cannot move between carriages except at stations, and fare evasion is a factor in Island Line’s revenue shortfall. The fare evasion is not always deliberate however – there are no ticket machines at most stations and passengers may be unable to pay because the guard is in the other carriage.

- Issues around power supply, signalling and infrastructure. The third rail also needs replacing and substations are in poor condition.

- Leasing costs for infrastructure from Network Rail to the franchisee are arranged so that costs increase towards the end of each lease period, adding to Island Line’s costs; the next period ends in 2019.

- Flooding remains a problem in Ryde Tunnel.

- Stations require modernisation to provide an appropriate, efficient, and pleasant retail and transport interchange experience.

- Ryde Esplanade in particular could see its connections with Southern Vectis buses and Hovertravel hovercraft much improved (plans for a substantial rebuild of the station and its interchange arrangements were abandoned in 2009 after costs rose).

- Taken together, SWR’s analysis suggests that what Island Line needs is the old Network SouthEast approach: a total route modernisation. The trains, track, power supply and signalling all need to be replaced, and the stations modernised, all at the same time.

Interestingly, no mention was made of any need for the Class 483s to meet the Rail Vehicle Accessibility Regulations by 2020. Presumably SWR is expecting a dispensation to be applied allowing for their continued use. However any new trains will have to comply.

What is Island Line actually for?

Part of the problem in defining the future of Island Line is that is there is confusion as to what its main purpose actually is. Recent operators have taken the view that it is primarily a tourist attraction, rather than a public service railway.

Network SouthEast treated Island Line as a conventional part of its network, despite its diminutive trains, with NSE branding applied to trains and stations (red lamp-posts etc) alike. But at privatisation, the first Island Line franchise saw trains painted in a tourist-friendly dinosaur livery, relating to the Isle of Wight’s rich fossil heritage and key tourist attraction Dinosaur Isle at Sandown.

A recent op-ed in the Island’s newspaper, the Isle of Wight County Press, criticised calls for the modernisation of Island Lane, praising instead its current tourist focussed operation. “Not only do you board a ‘step-back-in-time’ quirky old railway carriage but you bounce along the track with everyone springing up and down in their seats,” it said. “Island Line is one of our Unique Selling Points,” the piece concluded, “let’s make a feature of it.” The Isle of Wight’s official tourism website meanwhile sells the former London Underground trains as giving Island Line, “its very own unique identity and appeal.”

Yet Isle of Wight Council says what it actually wants is a “modern and extended Island Line that meets the needs of residents and cuts traffic congestion”.

Isle of Wight bus map (Southern Vectis)

Isle of Wight bus map (Southern Vectis)

The Isle of Wight has an extensive and high quality bus network, run by Go-Ahead subsidiary Southern Vectis. However its Routes 2 and 3 parallel Island Line over virtually its whole length, with the two routes combining to provide four buses per hour. But although the quality of the bus on-board environment is superior to that of the Class 483 in almost every way (most Southern Vectis buses have USB charging, many have Wi-Fi and the buses are getting next-stop displays/announcements), a comparison between bus and train journey times shows where Island Line’s unique competitive advantage lies.

On a weekday morning in peak time, the Route 2 bus takes 51 minutes from Shanklin station to Ryde Esplanade. The train does it in just 22 minutes. Both buses and private cars have to use the Island’s narrow, twisty, and (in holiday periods) heavily congested roads.

The present 20/40 minute train headways are hardly competitive, as the waiting time could be longer than the full bus journey over certain sections. If the train service were more frequent, or at least more regular, it would surely help generate more traffic.

Buses also cannot run along the weight-restricted Ryde Pier to meet the ferry, so the train has a further advantage. For travellers using the ferry, or trying to get between the main towns on the east of the Island, the train is faster and more reliable than any other option including cars, despite the less-than-contemporary passenger environment on board. So there is an ‘express’ travel niche that Island Line could usefully exploit, but this contradicts the actual impression given by the line’s current appearance as a tourist attraction and/or vintage travel experience.

Yet Island Line does carry regular commuter flows both within the Island and to/from the mainland (this writer uses it to get from Shanklin to his day job in Ryde), as well as schools traffic. Such passengers are unlikely to find the ‘heritage’ aspects of the way Island Line is currently operated appealing, and probably want a travel experience with a quality of passenger accommodation more like that of the local buses, or trains on the mainland.

What are the solutions? SWR’s view

The consultation document gave SWR a chance to put forward some ideas, and its preferred option, for the future of Island Line. Having considered Parry People Mover-type vehicles, conversion to a busway, new third-rail stock, tram-trains, overhead line-powered stock, self-powered stock and various combinations thereof, SWR’s preferred proposal was:

- A ‘self-powered’ – but not diesel – train, accommodated on the existing infrastructure.

- A 25-year lease to help spread costs.

- An enhanced service frequency to better connect with the hovercraft and catamaran ferries [presumably an even (30-minute) headway though this was not explicitly stated].

- Infrastructure improvements to allow better interchange between Island Line and the Isle of Wight Steam Railway to generate revenue for both organisations.

- Better marketing and revenue protection.

Running “on the existing infrastructure” is somewhat ambiguous. It is unclear whether SWR means the infrastructure exactly as is (such as no works to Ryde Tunnel, so any new trains could not be significantly taller than the current tube-style dimensions) or perhaps no route extensions at present, but not ruling out infrastructure changes to ease the height restrictions at Ryde Tunnel.

Meanwhile, self-powered but not diesel would suggest battery or perhaps flywheel power sources. It is improbable that Transport Secretary Chris Grayling’s latest favourite technology – hydrogen fuel cell power – will become rapidly practicable for what would be a very limited batch of small trains, without much at all in the way of roof space for hydrogen tanks.

The railway has a number of hills which could provide the opportunity for regenerative brakes to recharge batteries if a battery powered replacement train type is selected.

Other options

Garnett’s 2016 report suggested the acquisition of T69 trams from Centro’s Midland Metro operation, despite them being taller even than the Isle of Wight’s original steam stock, and requiring additional clearance for overhead power lines. It proposed conversion of Island Line to a tramway with a 15-minute service frequency and ‘line of sight’ operation to achieve savings through abandonment of the existing signalling equipment. However the proposal to use the ex-Midland Metro trams is no longer an option as Transport for West Midlands has just announced it has sold them for scrap.

The 2016 report also suggested handing over one of the two tracks between Smallbrook Junction and Ryde St Johns Road to the Isle of Wight Steam Railway.

Station strip map (author)

But the report was also controversial because it suggested removing Island Line from the wider franchise. This raised local concerns, particularly as the Department for Transport (DfT) had suggested in the South Western franchise consultation at around the same time that a social enterprise could run Island Line, and that it should be put on a ‘self-sustaining’ footing. It seemed impossible to identify a way that the line could ever be self-sustaining, and the wording was eventually changed to “more sustainable” in the final version of the franchise specification.

In any case, all of Garnett’s recommendations were ultimately rejected by the Isle of Wight Council.

During the SWR-led consultation on the future of Island Line in late 2017, a public meeting was organised on the Island by local campaign group Keep Island Line in the Franchise (KILF). This group wants to retain third rail as a power source and to make it fit for purpose, but they would accept a hybrid or battery train, provided that service levels are not diminished. KILF would also like to see an even 20 minute headway service, though it notes a 30 minute headway service would potentially offer better connections with ferries.

Re-openings?

However, the public meeting which took place in Shanklin on 14 December 2017 was overshadowed by the release of the DfT’s Strategic Vision for Rail a fortnight earlier on 29 November. On the mainland, the DfT’s suggestion of re-opening long-closed railways successfully (at least at first) diverted media attention from the recurrence of revenue problems at the Intercity East Coast franchise.

On the Island, the DfT’s sudden apparent enthusiasm for rail re-openings diverted attention from resolving Island Line’s current problems, resulting instead in Island crayons being broken out. Local press coverage of the public meeting majored on KILF’s longer-term aspirations for extending Island Line by reopening the line from Smallbrook Junction to Newport. This would be achieved by operating over the tracks owned by the Isle of Wight Steam Railway, which itself would need to be extended westwards from its current terminus at Wootton.

Several route proposals for such a reopening had been put forward by consultancy Jacobs in 2001, though at least one (with a street-running town centre loop in Newport) required tram-type rolling stock, and featured some heroically tight curve radii.

Although Newport is the ‘capital’ of the Island and the hub of the Island’s road network, it isn’t actually the largest town. Its population is slightly less than that of Ryde. The other big towns on Island Line, Sandown and Shanklin, have populations about half of Ryde’s.

The release of the DfT’s Strategic Vision for Rail also led to suggestions on the Island for reopening the line from Shanklin to Wroxall and Ventnor, an idea which crops up every few years despite the technical challenges of that reopening not having become any easier to solve in the meantime. The tunnel into Ventnor now houses a water main which would require an expensive diversion, and the track bed of the line has been built over at Wroxall and Ventnor stations.

The local MP took up the cause of Isle of Wight railway reopenings with some vigour in the House of Commons in January, asking Transport Minister Nus Ghani for a commitment to extend Island Line to Newport and Ventnor if feasibility studies confirm costs in the £10-30m range. However, he took an unusual approach in attempting to curry favour with the DfT by suggesting that such sums of money were equivalent to typical DfT margins for error in its accounting, and that his proposal compared favourably with the “very poor” returns offered by HS2. He made much less mention of the need to solve the existing challenges of Island Line’s immediate future, which SWR’s consultation had identified.

What Next?

Even the more realistic proposals, set out by SWR its consultation document and focussing on the existing route, face some daunting obstacles. It is hard to think of any off-the-shelf train capable of fulfilling SWR’s aspiration of being self-powered but non-diesel and capable of running within Island Line’s restricted loading gauge.

Ryde Tunnel (west end) & pump house (author)

The height restriction imposed by Ryde Tunnel rules out follow-on orders for any existing mainline train type in use on the mainland. It also would seem to exclude options like Vivarail’s ex-D78 District line ‘D Train’ stock, which is approximately the same height as mainline trains. Island Line staff have apparently visited Vivarail’s facilities to enquire about these trains’ suitability, but nothing has been officially stated about any outcomes. Nonetheless rumours persist of the island’s interest in these reburbished and rebuilt trains.

Island Line’s track was raised at stations during the electrification programme to allow impressively level access on and off the Tube stock (except at Ryde Esplanade, where the platform was lowered). In mainline train terms, platform heights are now at low floor rolling stock level. This further adds to the procurement challenge unless expensive track re-lowering is undertaken.

Were the track bed in Ryde Tunnel lowered to its original position, this might make any new Island Line trains easier to source. The original height restriction for the Island’s rolling stock equates to stock of a similar height to BR’s PEP-derived Class 313/314/315/507/508 series, which are slightly shorter in height than most British trains.

Lowering the track bed in Ryde Tunnel would, though, leave it more susceptible to the original flooding problem it was raised to counteract. The increased flooding risk might be mitigated with new pumping equipment, but new pumps would just introduce another yet cost pressure to the future of Island Line, both in terms of capital outlay and running costs.

And, as we have seen, this is not just a new trains problem. There is more to Island Line’s troubles than just the urgent need to replace the Class 483s.

Ryde Pier Head in 2018 (author)

Even apparently simple infrastructure projects to address obvious problems have additional costs. Reinstating the second track to create a passing loop at or near Brading station would be needed to achieve a regular 30-minute headway for train services, but it is not as straightforward as relaying the missing track. Lineside cabling has been placed on the old track bed, and would have to be relocated, adding to costs.

The power supply is at end-of-life stage with third rail and substations requiring replacement. Network Rail’s recent adventures in electrification give concern as to what the cost of this would be if like-for-like replacement were felt to be the best way forward. Meanwhile the track and track bed also need attention to bring them up to modern standards of ride quality, with considerable cost financially and in terms of service disruption. Island Line can ill-afford to put off passengers with lengthy closures for engineering work.

Though perhaps less easy to quantify in cash terms, if the decision is taken to de-electrify Island Line and use self-powered trains, what message would that send? Whilst the current Transport Secretary appears to be no fan of rail electrification, having cancelled several planned projects and curtailing others around the country, de-electrifying an existing electrified route would be another thing altogether.

SWR’s consultation ended on 31 December 2017, and it has until 31 May 2018 to submit a costed proposal for the future of Island Line to the DfT. Regular meetings of a Steering Group comprising Isle of Wight Council, DfT, Network Rail and SWR are now taking place (albeit not in public) which will shape the final proposal. According to SWR’s franchise agreement, that proposal must be “capable of acceptance by the Secretary of State”. Given the peculiar decisions of the current incumbent of that post, what might constitute acceptability is open to some degree of uncertainty.

To keep the line, targeted investment is needed

Underlying all this is that Island Line is not in itself a profitable operation. Replacement of trains and infrastructure add substantial costs without necessarily adding anything to income, worsening Island Line’s accounting position. With annual revenues of around £1m, at what price do the works necessary to secure Island Line’s long term future cease to represent value for money?